A Rebuttal to Varoufakis' Ranking of Antisemitism as 'the Vilest Among All forms of Racism"

All due respect, Yanis, but refrain from ranking racism.

By Karim Bettache

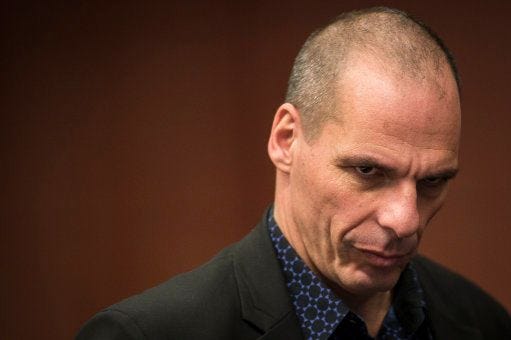

My journey toward understanding the universal struggle against racism has often found me crossing paths with the words of Yanis Varoufakis, a renowned economist, professor, and former Greek politician. Known for his passionate advocacy for the marginalized and his vocal stance on social justice and equity, Varoufakis's insights have often resonated in the numerous interviews I've encountered.

However, one particular assertion by Varoufakis has repeatedly surfaced, a statement that I've heard him express multiple times across different platforms: his belief that anti-Semitism is "the vilest form of racism". While I greatly respect his commitment to challenging injustice, this specific viewpoint has increasingly unsettled me. I've found myself returning to it over and over again, reflecting on its implications and the message it communicates about the various forms of racial violence and oppression that have scarred our collective history.

And now, I find that I cannot remain silent any longer. It's time for me to articulate my response, to voice my disagreement and to contribute my perspective to this critical discourse. It's crucial that we engage with these difficult conversations in a way that does justice to all victims of racism, without unintentionally creating hierarchies of suffering.

While the horrors of anti-Semitism are undeniable, and the battle against it is of paramount importance, the inadvertent implication that some forms of racism could be ranked in terms of vileness is deeply problematic.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to BettBeat’s Newsletter to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.