Evil versus Stupid

Explaining U.S. foreign policy via political psychology

Once upon a time, Fox News ginned up a scare campaign about a mosque. They insinuated that a funder of the proposed mosque, a Saudi prince, had terrorist designs - while failing to mention that the same prince was a part owner of Fox News itself. Debate ensued over the two available explanations for this, ending in a compromise. John Oliver conceded that “if they’re not as stupid as I believe them to be, they are really fucking evil.” And Wyatt Cenac followed suit with “if they’re not as evil as I think they are, they are stooopid - we’re talking potatoes with mouths.”

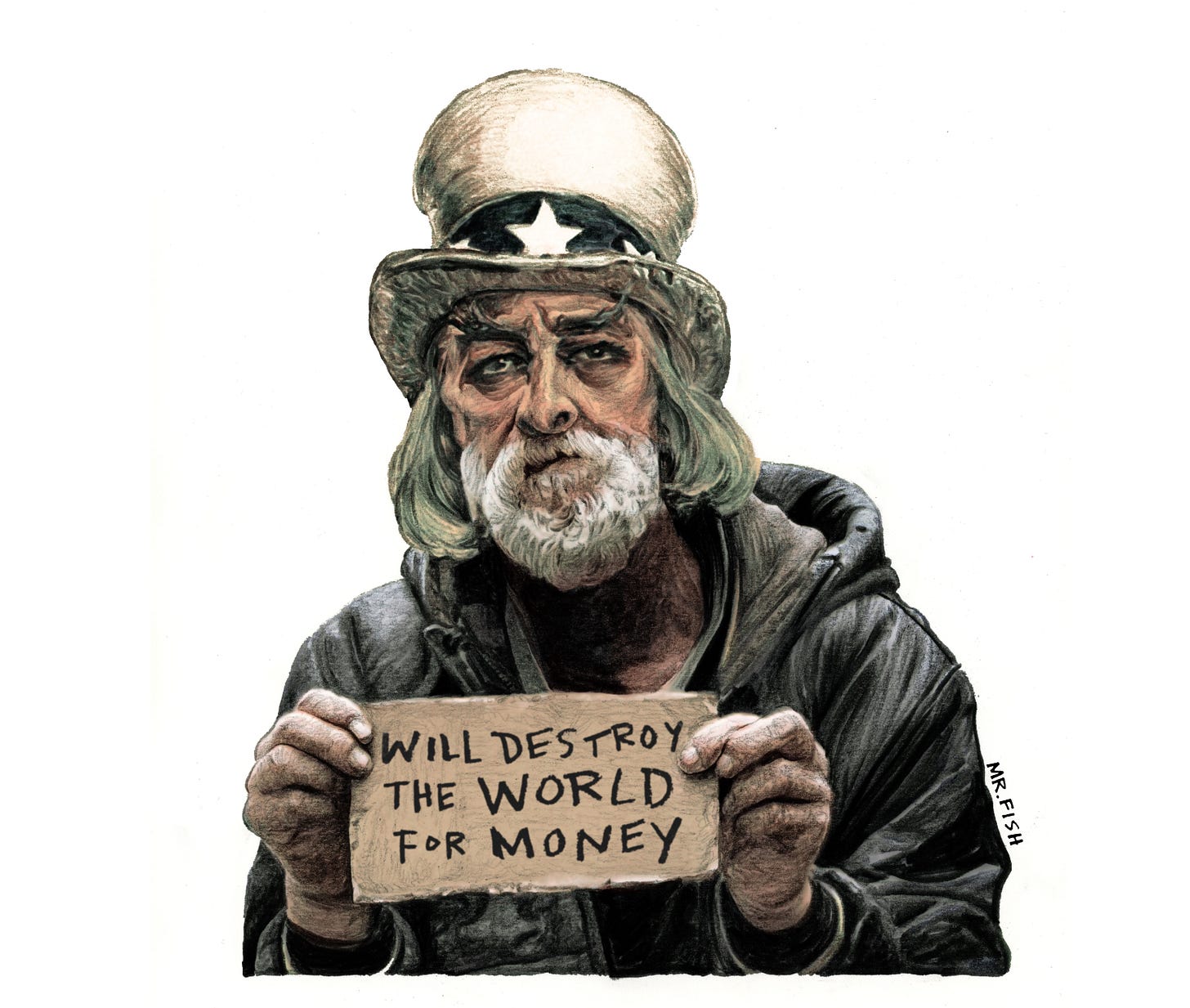

“Really fucking evil potatoes with mouths”? Wait… is someone talking about the Blob, the U.S. foreign policy establishment? (That is, the revolving door of think tankers, government officials, weapons company employees, and academics who have led U.S. foreign policy from one bloodsoaked disaster to another.) Because that question - are they evil, or just stupid? - has bedeviled me for decades. I have an answer; but first, some background. I’ll introduce a bit of Blob thinking (or “thinking”), and then decide whether Team Stupid or Team Evil has the better explanation.

One of the many, many ways in which this past year has been depressing is finding myself forced into the position of defending John Mearsheimer and the “realist” school of thought in international relations* (IR) scholarship. For the blissfully ignorant, IR realism is a theory or ideology starting from the observation that international politics is anarchic. In domestic politics, societies create a Leviathan – the government – to monopolize violence. Because there are so many small bullies running amok in society, we create a big bully, government, to discipline the small bullies. But in international politics, there is no higher authority to turn to. If a country is invaded, it cannot call the police, it can rely only on itself for defense. That’s “anarchy”. From this comes the descriptive part of realism: since countries must rely on “self-help”, they try to maximize their power above all other considerations (like morality). And from this follows the prescriptive part of realism: countries should focus exclusively on power maximization, just in case a neighbor were to invade. What about other goals, like strengthening the U.N. to reduce the threat of anarchy, or maximizing quality of life and ensuring economic equality worldwide? Why that’s “idealism”, and it’s bad! Any bit of effort or resources spent on these “idealist” goals is an increment of potential national power squandered. Governments should act like rat bastards, single-mindedly pursuing power maximization above all else. That may sound immoral, to the uninitiated, but no! Spending resources on the poor of the world (or other frivolities) is what’s immoral, because it comes at the cost of maximizing national power, thereby risking national extinction. It’s Eisenhower’s “Chance for Peace” speech in reverse: every homeless person housed, every hungry person fed, every child educated signifies, in the final sense, a theft from the armory not overflowing with weapons, the naval shipyard without a new aircraft carrier, the weapons company investor without a McMansion in Fairfax.

There are plenty of flaws in realism, starting from its very roots. Long story short, it’s laughably out of step with today’s understanding of science. A scientific realist would acknowledge that the desire for security via power maximization is a powerful force operating in the complex system that is international politics - probably the most powerful - but that’s it. There are no “laws” in the social sciences, no “the” explanation, only forces and tendencies. So a scientific realist would concede the descriptive side of IR realism - yes, governments have tended to act like rat bastards, maximizing their power by hook or by crook - but would laugh at the prescriptive side for being unscientific; or, if you like, unrealist. (“Realism” is incontestably unrealistic when its proponents ignore the ecological crisis.)

Problem is, as much as I dislike the prescriptive side of realism, I don’t have a good argument against its descriptive side. Governments have indeed tended to act like rat bastards, single-mindedly maximizing their power whatever the human cost. Leftists are IR realists, in the descriptive sense.

Then came the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Finally, Western mass publics and elites were united in deep concern for the victims of war, and in opposition to flagrant violations of international law. (Well, at least for some victims of war, and one flagrant violation of international law.) This is good in itself, and would be even better if the same moral outrage arose over every war. Another positive development: people started hating IR realism. Sadly, the hate IR realism recently generated was focused on its descriptive side, where realism is pretty much unimpeachable.

Intergroup bias is strong between the U.S. and Russia today: we, of course, are the good guys, and they, as always, are the bad guys. But if we are good, and they are bad, how to respond to the bog-standard IR realist analysis that U.S. policy toward Russia, NATO, and Ukraine was recklessly provocative? (Obvi, provocation ≠ justification. And if you aren’t already familiar with this argument, it’s time to become one of the 2% of readers who click through a link.) Haven’t similar ideas been expressed by Putin himself? (Meaning: they must be wrong.) Provocation is what bad guys do, not good guys like us - so this IR realist argument produces cognitive dissonance. How to reduce this icky feeling?

First, mass publics in Western countries most likely never heard the argument at all, since mass media rarely present it. So, no cognitive dissonance to reduce. But for those who do encounter the argument, the icky feeling of cognitive dissonance can be reduced in a number of ways. IR realist analysis doesn’t apply, because NATO is a defensive alliance. Phew, we are unambiguously good guys after all! Just don’t think too much about uncertainty, or how our perceptions are irrelevant because defensive/offensive is in the eye of the beholder.

Another popular way of reducing cognitive dissonance is the madman imperialist theory. Yes, IR realism may accurately describe international politics as a brutal arena of immoral power maximization blah blah, but in this one case, it’s irrelevant, because Putin is an imperialist madman, or madman imperialist - look at these speeches of his, what a psycho! This theory has some strength, since Putin has been a piece of shit since the New York Times was advising its readers to “keep rootin’ for Putin”. The problem with the madman imperialist theory is that it’s superfluous. It’s superfluous because the IR realist theory already explains his decision to invade. More importantly, every time a government has decided to prey upon foreigners, the stated reasoning of its top officials was never a simple “we’re strong, they’re weak, so we conquered them to amass even more power.” There is always some rationalization used to gild the lily (or, what seems more fitting: gild the pile of corpses). Do we take seriously British or French claims that their imperial predations were truly intended to bring the light of civilization to benighted peoples around the world, rather than merely amass more power for themselves? If so, I have a Greater East Asian Co-Prosperity Sphere to sell you.

To put IR realism into scientific realist terms: the desire to maximize power is the most influential force operating in the international system, so it is always the prime suspect for state behavior. Other forces exist, and can exert influence - like dreams of reconstituting the Russian empire - but there needs to be compelling evidence that such lesser forces are in the driver’s seat in any given instance, evidence indicating that the default IR realist explanation is, in this rare example, inapplicable. Why does this matter? Because if the standard IR realist explanation is accurate - in simplified form, that the primary motivation for the Russian invasion of Ukraine was to prevent its incorporation into the U.S. sphere of influence, including a military alliance - then the U.S. government could likely end the bloodshed by giving up this bid for more power. If the madman-imperialist theory is accurate, however, this option is an illusion.

Then there’s the moral indignation route to cognitive dissonance reduction. Agency, agency, agency - why, bringing up the best available explanation for government behavior is “denying agency”! That is, by focusing attention on the most powerful states in the international system, one is treating Eastern European countries as mere pawns. But this confuses the descriptive - in the international system, weak countries are treated like pawns by powerful countries - with the prescriptive, that weak countries should be treated as pawns. The core of the left critique of IR realism is that descriptively, it is accurate - and that is precisely the problem to be solved. But the don’t-deny-agency crowd sidesteps reality entirely, essentially arguing that since we wish we lived in a system in which weak countries were not treated as pawns, then by imagining that this ideal were already reality, it might become so. From their lips, to god’s ears. Davids Graeber and Wengrow recently wrote that “agency” is “the preferred term, currently, for what used to be called ‘free will’.” To avoid being dragged down the free-will-debate rabbit hole, would it make it any better if we rephrased Thucydides’ classic statement of IR realism such: “The powerful have the agency to do as they will, and the weak have the agency to suffer what they must”? Basta with the “agency” twaddle.

But let’s leave this background aside, and move on to the key question: is the Blob (the bipartisan U.S. foreign policy establishment) evil, or stupid? I’ll argue both sides.

First, the case for evil. This is an easy position to argue; just focus on the results of U.S. foreign policy, and ignore intentions (or assume that the results were intended). 4,500,000 human beings dead as a result of the global war on/of terror. 6,000,000 human beings dead as a result of covert actions in the Cold War. That very partial kill count is already over three times that of God’s, in His entire career! And it doesn’t include a host of other evil actions. If you go through the alphabet, by my count there is only one letter, Q, which is both a) the first letter of the name of a country, and b) in which the U.S. government has not committed an anti-democratic or anti-human-rights intervention (coup, assassination, torture, election meddling, etc.) since WWII. Experts on U.S.-Qatar relations: please correct me, if need be. And if Wakanda were a real country, the U.S. government would have nuked it as soon as the CIA discovered its vibranium and advanced technology (a dictatorship which posed a dire national security threat, we would be told as the fallout spreads around Africa). Killmonger was right.

The case for stupidity is a bit harder. So first, let’s define our terms. Ignorance is the state of not knowing something; it is not coterminous with stupidity. All of us, myself included, from Albert Einstein to U.S. cable news hosts, are ignorant of 99.9x% of all knowledge. Einstein may have been ignorant of only 99.99%, and Fox/MSNBC hosts ignorant of 99.999999999%, but regardless, our ignorance far outstrips our knowledge. This is unarguably true: just think of what the realm of knowledge encompasses. Every entry in an encyclopedia or Wikipedia is just a tiny fraction, as there are countless books, articles, and lectures on each topic, plus excluded topics; there is knowledge contained in only one or a few human brains, and knowledge that has been lost forever; knowledge about the trillions of planets in hundreds of billions of galaxies that we may never learn; plus knowledge of all the unknown unknowns I cannot even think of. Stupidity is not ignorance, it is something else.

Stupidity can be a brain that is inept at processing information. But I dislike this definition, because every time I’m flummoxed by simple division or multiplication, let alone subtraction, and turn to a calculator - well, you get the point. Stupid is as stupid does? That’s more personally flattering (most of the time), but I prefer defining stupidity as a characteristic of one who should have known better. Stupidity is shouldhaveknownbetterism, if you will. Getting back together with that toxic ex? That’s stupid, should have known better. Driving drunk? That’s stupid, should have known better. Trying the same thing over and over, expecting a different result? That may be insane, but it’s also stupid, because one should have known better.

So by this definition, is the Blob stupid - is it shouldhaveknownbetterist? A thousand times yes.

Let’s review how the average Blob corpuscle forms. There are exceptions of course, but we’ll just look at the typical social and psychological forces in operation. A child is born in the U.S., most often in a family with resources. The child learns from its parents that they are Unitedstatesian, as opposed to other nationalities - and that’s all intergroup bias needs to set in. The child goes to school, and learns a flattering account of U.S. history. Oh yes, there is so much CRT and woke in schools these days, I’m sure. But even if this child is taught indisputable facts about the native genocide, slavery, mass murder in the Philippines, the Banana Wars, KKK death squads, etc., this is counter-balanced with a bunch of buts: but the democratic experiment! But the abolitionists! But the suffragettes! But the civil rights movement! And fair enough, these are facts too; but intergroup bias skews the way we process this information. Abolitionists, suffragettes, and civil rights activists come to be seen as representative of the U.S. ingroup as a whole, while genocidaires, slavers, and imperialists are seen as the few bad apples, the exception to the rule.

In high school, as the child is halfway through its metamorphosis into a Blob corpuscle, it learns that the U.S. had a come-to-Jesus moment: either around WWII, or for those in woker schools, perhaps, at the end of the Cold War. (In less awoke schools, the Civil War.) Sure, in the bad old days, the U.S. ruling class comprised a bunch of white supremacist, sexist imperialists. But then we came to Jesus, so it’s all good now. We don’t even have a ruling class anymore; we have a meritocratic democracy, where even a Latinx cisgender millennial woman with imposter syndrome can become a CIA Director employee.

In college, the nearly complete Blob corpuscle faces one last threat to its development: a choice to take classes, make friends, or read books that may challenge their worldview. But even if they make this fateful choice, there is still hope - because learning information that contradicts existing beliefs will cause uncomfortable cognitive dissonance, and the easiest way to reduce it is to reject the new information. That professor, classmate, or book must be wrong! Or as John Kenneth Galbraith put it, “Faced with the choice between changing one's mind and proving there is no need to do so, almost everyone gets busy on the proof.” Plus, if this Blob-corpuscle-in-development is a striver, they’ll have lots of other concerns on their mind, too busy to bother with proof. This one dissident source is right, and everything I learned from parents, teachers, and TV is wrong? Nearly all our top politicians are monsters, not only those from the Bad Party? Why waste time investigating such an unlikely possibility!

Or, they take an intellectual vaccine - say, a class on IR, in which they learn first that the world is a nasty and brutish place; so yes, the U.S. government has gotten its hands a bit dirty now and then, but only because it had no choice in such a sinful, fallen world. For instance, aiding the massacre of 500,000-1,000,000 human beings in Indonesia: if “we” didn’t help murder all of those people, something far worse might have happened! This is exciting, learning dark secrets that ordinary muppets don’t know. And since it was all for the greater good, it doesn’t cause any icky cognitive dissonance. We’re still the good guys, even if we did have to break some skulls to make an omelet. Later, if the developing corpuscle does choose to take that class, make that friend, or read that book critical of U.S. foreign policy, they will be inoculated. Instead of facing cognitive dissonance between a rosy view of their national ingroup and the critique of its murderous foreign policy, they can brush aside the critique as a simplistic, blame-America-first polemic ignorant of the bad choices facing good guys in a world of anarchy.

By the time this corpuscle has found a home, assimilated in the Blob at a think tank or government agency, it is well equipped for stupidity. Ignorance of critical arguments and the evidence on which they are based: check. Exculpatory worldview, in which evil can be good so long as it is done for a good cause: check. Social network of like-minded peers who will never challenge core beliefs: check. Media diet lacking diverse ideological perspectives, foreign and domestic: check. And, of course, something we all share: an evolved psychology with biases tending to preserve preexisting beliefs in the face of contrary evidence, and intergroup bias skewing our perception of national ingroups and outgroups. (Not to mention: ours is a psychology adept even at self-deception.) Hence Orwell’s line: “The nationalist not only does not disapprove of atrocities committed by his own side, but he has a remarkable capacity for not even hearing about them.”

This is stupidity as shouldhaveknownbetterism. Blob corpuscles receive excellent schooling (if not education). Even though they typically don’t, they had every opportunity to engage in self-reflection, and wonder by what magic the ruling classes of every other empire believed in self-serving falsehoods, but they uniquely were spared. We’d ridicule a Roman senator, transported to the present, arguing that the Roman empire was devoted to a selfless mission to bring civilization and peace to the world. Or a Mongol councilor, a Dutch East India Company executive, an imperial Japanese newspaper editor, a French governor-general, a British colonial official, and so on, making similar claims about their own empires. Such claims, we would correctly recognize, are utterly laughable. But Blob corpuscles believe that their contemporary claims about the U.S. empire, of the exact same sort, are valid? This is stupidity.

Blob corpuscles had every opportunity to learn about psychology, and apply this knowledge to their own thinking. What, I wonder, does intergroup bias do to our thinking about international politics, the realm of ingroups and outgroups? How might this bias affect the supply of information I rely on to shape my picture of the world? Given the existence of groupthink, should I be a little bit concerned about the ideological homogeneity of my peers, my media diet, my fellow Blob corpuscles? Naaah! We’re right, and everyone else is - conveniently - wrong.

So yes, I am on Team Stupid. But with stupidity like this, in possession of so much power… stupid versus evil is a distinction without a difference.

* If you read only one book on IR, I recommend Shiping Tang’s The Social Evolution of International Politics. It provides a good introduction to IR theories, and unlike all of the alternatives, puts IR into true historical context: not starting 500 or 2,000 years ago in Europe, but hundreds of thousands of years ago in Africa.